Shock from blood loss is classified as hypovolemic shock, which basically means that there is not enough fluid (blood) circulating throughout the body. Without an adequate volume, organs such as the kidneys and GI tract are not being perfused (nourished), and this state can quickly turn deadly. Your veterinarian can tell if your dog is in shock by physical exam findings such as a high heart rate, a low blood pressure and weak pulses.

Did you know the loss of as little as 2 teaspoons of blood per pound of body weight can result in shock? This blog post describes ways to control bleeding in your pet during transport to your nearest veterinary hospital.

The following techniques are listed in order of preference. As a word of caution: The first rule when dealing with an injured pet is to avoid injury to yourself. Take appropriate precautions, such as the use of a muzzle, to avoid being bitten. You can create a “make-shift muzzle” by using a long piece of material such as a men’s tie, non-retractable leash or piece of cloth. All too often, I see owners having to make a trip to the emergency room for themselves as well as their pet.

The best way to learn these techniques is in a pet first aid class. April is Pet First Aid Awareness Month,

a perfect opportunity to sign up for pet first aid classes, which are

offered by local chapters of the American Red Cross, some shelters and

humane organizations. Also, it's a good reminder to have a complete pet

first aid kit (which includes a muzzle) among your dog supplies.

The best way to learn these techniques is in a pet first aid class. April is Pet First Aid Awareness Month,

a perfect opportunity to sign up for pet first aid classes, which are

offered by local chapters of the American Red Cross, some shelters and

humane organizations. Also, it's a good reminder to have a complete pet

first aid kit (which includes a muzzle) among your dog supplies.Direct pressure

Direct pressure on a wound is the most preferable way to stop bleeding. Gently press a pad of clean cloth, gauze or even a feminine sanitary napkin over the bleeding area: this will absorb the blood and allow a clot to form.

If blood soaks through, do not remove the pad. This will disrupt the clot; simply add additional layers of cloth and continue the direct pressure more evenly. The compress can be bound in place using loosely applied bandage material, which frees your hands for other emergency actions. If you don’t have a compress, you can apply pressure with a bare hand or finger.

Elevation

If a severely bleeding wound is on the foot or leg, and there is no evidence of a broken bone, gently elevate the leg so that the wound is above the level of the heart. Direct pressure of the wound must be continued in addition to elevation.

Elevation uses the force of gravity to help reduce blood pressure in the injured area, slowing the bleeding. Elevation is most effective in larger animals with longer limbs because of the greater distance from the wound to the heart.

Applying pressure on the supplying artery

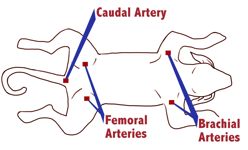

Applying pressure on the supplying arteryIf external bleeding continues after you have used direct pressure and elevation, you can use your finger or thumb to place pressure over the main artery to the wound. For example, if you have severe bleeding on a rear leg, you would apply pressure to the femoral artery, which is located in the groin (on the inside of the thigh). If you have severe bleeding of a front leg, you would apply pressure to the brachial artery, which is in the inside part of the upper front leg.

Tourniquet

Use of a tourniquet is potentially dangerous and should only be used for life-threatening hemorrhage in a limb. If you see blood spurting or pumping from a wound, which, luckily, is a rare occurrence, consider the use of a tourniquet.

Use a 2-inch wide piece of cloth or leash, and wrap it around the limb twice and tie it into a knot. Then tie a short stick or similar object into the knot as well. Twist the stick to tighten the tourniquet until the bleeding stops. Secure the stick in place with another piece of cloth and write down the time it was applied. Every 20 minutes loosen the tourniquet for 15 to 20 seconds. This is potentially dangerous and can result in the need to amputate the limb. Remember, a tourniquet should only be used as a last-resort, life-saving measure.

Internal bleeding

Internal bleeding is another form of potentially life-threatening blood loss, where blood pools in the abdominal or chest cavity, but does not result in visible blood in the stool or bleeding from the rectum. A few causes of internal bleeding include rat bait poisoning, ruptured masses on the spleen, trauma and sometimes in the case of immune-mediated disease.

Internal bleeding can often be more dangerous because it occurs inside the body, and being less obvious, delays evaluation by your veterinarian. There are, however, some external signs of internal bleeding, which can include any of the following:

- Your pet’s gums appear pale to white.

- Your pet feels cool on the legs, ears or tail.

- Your pet is coughing up blood or having difficulty breathing.

- Your pet is unusually subdued; progressive weakness and sudden collapse may be observed.

- Your pet has a painful belly when it is touched.

No comments:

Post a Comment